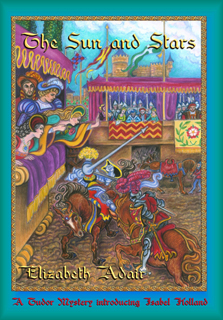

The Sun and Stars by Elizabeth Adair

Isabel Holland, illegitimate daughter of King Henry VIII, walks a privileged but precarious road through the intrigues of the Tudor court. When her cousin Sir Hugh Lovell is accused of stealing the prized crown known as the Sun and Stars and murdering its guards, Isabel pits her family loyalty against the political plotting of formidable opponents Cardinal Wolsey, Thomas Cromwell and the ruthless Lord Adam Colford. A young woman without official status, she discovers more murders and their connection to a conspiracy far more vast than a simple theft. Isabel realizes she is the only one who can save her cousin from execution and expose a plot to betray the King and the future of England.

Isabel Holland, illegitimate daughter of King Henry VIII, walks a privileged but precarious road through the intrigues of the Tudor court. When her cousin Sir Hugh Lovell is accused of stealing the prized crown known as the Sun and Stars and murdering its guards, Isabel pits her family loyalty against the political plotting of formidable opponents Cardinal Wolsey, Thomas Cromwell and the ruthless Lord Adam Colford. A young woman without official status, she discovers more murders and their connection to a conspiracy far more vast than a simple theft. Isabel realizes she is the only one who can save her cousin from execution and expose a plot to betray the King and the future of England.

King Henry lifted his hand. All eyes fixed on it, and all breaths halted. Suddenly, he signaled. With a glitter of armor and thunder of hooves, the two knights charged. Lance struck shield and splintered with a loud crack, the fragments sailing into the air. With a rending crash the defender hit the ground, but his esquire dashed to help him up, and at once he drew his sword. His opponent dismounted, swept out his blade and attacked. Metal clanged, and the defender staggered, but his blow struck home, veering them both around. His second stroke went wide for the sun in his eyes. Seeing this, the challenger shifted again, giving up his unfair advantage and winning the crowd’s cheers for his chivalry. But he spared his opponent no other quarter. Gauging himself the stronger, he elected to take the next blow full-on. Then his stroke crashed down, felling the defender. Lying on the ground, Sir Edward Nevill raised his visor to signal himself beaten.

King Henry VIII applauded both his boon companions as the Duke of Suffolk helped his opponent up. Nevill smiled at his defeat with good grace. His red hair and large face looked remarkably like his kinsman the King’s.

“You won the first wager.” Isabel Holland turned to her cousin.

Sir Hugh Lovell grinned. “I told you.”

“Well then, Sir Oracle,” she challenged, “predict the next.” She exchanged a glance with their friends, Jane Giffard and Sir Thomas Wyatt. Hugh was opinionated, and teasing him good sport, but his advice might be worth a wager. He would be making a brave show today himself, but for the wrist he had injured during practice.

“Not so straightforward from now on,” her cousin answered. “Last night’s rain soaked into that gravel. The horses’ hooves are starting to expose patches of mud.”

“And they’ll be sliding like skittles.” Isabel made light, but misgiving seeped into her exhilaration. She surveyed the tiltyard. The shadows of the gay pennants fluttered over dark streaks where the gravel was damp. A breast-high wooden barrier divided the ground to protect the jousters and their mounts from collisions and flying hooves, but even in play, combat could be fatal.

Hugh flexed his sprained wrist slowly, disgusted at his luck. It was strong, sturdy of bone and sinew, the hairs on it as fair as those on his head. He was vigorous and strapping, with a short nose and blue eyes. Isabel did not resemble her cousin. She was slender and of middling height. Her face would do, but it had neither the white and rose complexion nor the spiritual otherworldliness men admired most. She prided herself on her wide-set grey eyes and the contagious lilt of her laughter, but she would have given half her land for splendid red hair. Hers was light brown, a tawny gleam its only hint of her Tudor blood. She took after her mother, by all accounts. She would never know for herself. Twenty years ago, a young lady-in-waiting had surrendered her virtue to handsome young Prince Henry, and gotten for it a babe but no husband, and death in childbed.

Isabel looked across the crowd of courtiers to where her father sat beneath a velvet canopy. His massive vigor gleamed larger than life. His doublet of cloth of gold was trimmed with garnets and set off by silken hose of a delicate yellow. On his head shone the Sun and Stars, the crown fashioned from gold he had captured in France. Whiter than the sun its huge diamond blazed, surrounded by constellations of smaller rubies, sapphires and amethysts. Yet, brilliant as his jewels shone, his golden-red hair rivaled them. His face was large, his features small, regular, and at the moment lit by a smile as expansive as the fair day that had freed him from a long imprisonment indoors. A wet May had thwarted his will, and King Henry took ill any thwarting, even by the heavens.

Yet he was not merely a hunter and athlete. He relished an argument in Latin as much as a competition with the bow, and when Isabel turned old enough, a tutor from Plymouth came to stay at the manor in the rolling uplands of Devon where her grandparents raised her. She’d had a stringent education for a girl of the country gentry, and when old enough was summoned to court to wait on the Queen.

Isabel glanced at Queen Katherine sitting by the King. Her proud Spanish decorum concealed a troubled mind. Isabel’s existence was not the only proof of King Henry’s interest in ladies other than his wife. Besides her brother, Henry Fitzroy, it was rumored that at least one of the children of Sir William Cary’s wife, Mary Boleyn, was fathered by the King. Affection for her husband’s bastards could not be expected, yet Isabel could attest to the Queen’s graciousness. She would be watching today’s tournament among the Queen’s maids of honor, if not for the King’s broad hint that she should take time off. It was not Isabel who need fear her royal father’s displeasure, he’d intimated. In all their years of marriage, the Queen had borne only one surviving child, Princess Mary. The throne lacked a legitimate male heir, and gossip raged that King Henry was secretly at work to annul his marriage.

Yet, a secret tattled about by all the court could hardly be secret from Queen Katherine. That was the meaning of her father’s hint. Trouble was brewing, and Isabel should take care not to be caught on the wrong side. The loyalty she owed the Queen being duty only, Isabel had vacated the palace with a clear conscience. With the rains of April muddying the Devon hills and turning the Torridge to churning brown floods, the remote countryside held few of the attractions it would in high summer. Isabel had moved in on her Aunt Margery, Hugh’s mother, in London.

“I see you gawping at the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting,” Jane teased Wyatt, whose glance had followed Isabel’s.

Wyatt smoothed his short brown beard with a restless finger. “That I am not,” he answered indignantly.

“Thomas is a poet,” Isabel added, “and so, incapable of gawping . . . though it might be wise to gawp a little less at Mistress Anne.”

Wyatt pointedly refused to answer. But Jane sniffed. “Anne Boleyn? She’s skinny as a switch and has hair like crows’ feathers. What King Henry sees in her is beyond me. Now as to the gentlemen in the royal party, there’s one I’d hoped to see. What a disappointment the French ambassador’s secretary is in bed with the rheums. Have you noticed him, Isabel?”

“The round one, like a little capon?” Isabel could not resist baiting her. Every handsome new gentleman at court turned Jane’s head. Isabel just hoped her friend’s parents wouldn’t marry her to some man with brows of a monkey or the teeth of a horse.

“What do you take me for? No, the slim, dark eyed one, of course. Monsieur Des Roches.”

“With the point to his beard, like Mephistopheles.”

“Does no man find favor with you?”

Isabel frowned. “I’m no condemned soul—yet. I’ll put off thoughts of marriage until I’m commanded.” She turned to her cousin. “Well, Hugh? What have you wagered on Tom Seymour?”

“Seymour?” Hugh smiled. “Nothing. Lord Colford will best him.”

“Never!” Isabel answered, stung. “He’d better not, I’ve bet two marks on it,” she added quickly. That evening in the garden last October must not be guessed. Tom Seymour’s compelling eyes, the scent of him like leather and smoke, and the heat of his lips on hers could send them both into exile and disgrace if gossip caught wind of it. Though his family were West Country gentry like her mother’s, she knew right well her father would never countenance such a match. Tom was a younger son with few expectations but what he could make for himself, and though he’d demonstrated soldierly bravery, Isabel had to admit he’d showed few signs of prudence. Since then, she’d avoided him. At least she’d see him again now, if only from afar.

“What, Hugh?” Wyatt asked. “Since when is it your habit to back your enemies?”

“Colford was no gentleman in France,” Hugh acceded, “but he’s shrewd, and more seasoned than Seymour. I back winners.”

Braying rent the air, a horrific, discordant sound, yet it slyly managed to bring to mind the trumpets of a royal fanfare. Through the near archway ambled a bizarre figure. Mounted on an ass, he wore an overturned wooden bucket for his helmet, and for his breastplate, a crockery platter. His steed was equally splendid, its caparison a bedspread and the mount itself no less than a unicorn, as proved by the carrot tied to its poll. As knight and steed passed below the stands where Isabel and her friends sat, the ass planted its hooves, threw back its head and protested stridently. The rider flourished aloft his lance, a scraggled broom, but the ass sat down, delivering the warrior rump down in the gravel. Untroubled by this misfortune of war, the valiant doffed his bucket and leapt into a cartwheel, patched buskins and shining gauntlets spinning.

“Will!” Isabel called amid the laughter and catcalls of the crowd. “Noble Sir William, Champion of the Joust!”

Picking out the sound of her voice, Will Somers faced her and bowed solemnly. Nothing abashed, Isabel rose and returned a blithe curtsy, to the cheers of courtiers and commoners. Like the jester, she was a favorite at court. King’s jester and King’s pet bastard, many took one no more seriously than the other. Since childhood she had sensed her place was privileged, but inconsequential. In the end, her father would marry her off as a reward for some man’s loyalty, or an inducement where loyalty was uncertain. Never officially recognized by her father, she did not have any particular legal status. Like Will, she could only prosper by pleasing. Because of this, they had always shared an unspoken alliance.

Will cupped a hand to his ear, hearing some elfin challenge inaudible to the coarser senses of the crowd. Retrieving his lance, he brandished it fiercely and leapt astride his unicorn, but the saddle slid until he hung upside down. The onlookers roared with laughter as clinging to the ass in this indelicate embrace he trotted from the yard, roaring with all the fury of a thwarted Mars.

“That takes skill,” Hugh said, grinning. “I’ve always said Master Somers would have made a champion if a lowborn man weren’t forbidden to bear a knight’s arms.”

“Methinks he finds ways to even that score,” Isabel returned, applauding as Will disappeared through the archway with an upside-down parody of knightly hauteur.

“Look.” Hugh hushed his voice. “Here’s an entrance not unlike that exit.”

Outside the low wall, servants wearing Cardinal Wolsey’s badge were cleaving a passage through the common folk. The path they forced was unnecessarily wide, and displaced people who had stood all day to get their vantage point. Some shouted and shoved back, but subsided to resentful quiet as the gentlemen of the Cardinal’s household marched into sight as grandly as if in the train of the Pope himself. The Cardinal’s secretaries followed, then two attendants, one bearing the velvet purse containing the Great Seal of England, the other carrying a pillow upon which sat the Cardinal’s scarlet hat. Finally, in full red robed regalia, came Cardinal Wolsey himself. He paced with measured tread by reason of his vast dignity, and no doubt also by reason of his vast bulk. His expression was of supercilious disregard, and as he passed through the common people he held to his nostrils a pomander of orange peel stuffed with spices, to save him from smelling their sweat.

“Detained by matters far more important than the King’s pleasure, no doubt,” Jane whispered. Her cautiously lowered voice was wise. The Cardinal had many spies. “I hear the Duke of Norfolk himself had to ask three times before Wolsey granted him an audience.”

“What, only three?” Wyatt quietly bantered. “I call that gracious, in a priest who’s richer than the King. Even the Pope begs his table scraps.”

“A most studied lack of study,” Isabel agreed, as the Cardinal mounted into the stands, sparing not a glance for his ecclesiastical peer, the Archbishop of Canterbury. He reached the chair that awaited him, canopied by a scarlet baldachin nearly as elaborate as the King and Queen’s. Not until he was settled did his gentlemen permit themselves to sit.

“They say his cardinal hat is specially made in Paris,” added Jane.

“English dye isn’t scarlet enough for him,” Hugh rejoined, and challenged Isabel, “Cap that, coz.”

“Nay, a cap that red’s too hot to touch,” Isabel answered. “And it caps a hellfire of ambition. Yet, he has one good friend.” She would not, and need not, speak clearer. Her father depended all too utterly upon the Cardinal’s administrative genius.

The trumpets cried forth, and Isabel fixed her eyes on the near archway, the crowd shrinking to a tiny, droning insect in her awareness, and the entrance for the defenders’ team looming to the consequence of a portal of heaven or hell. At last, Tom Seymour rode into the lists, proud in his armor, his almond eyes determined beneath his raised visor. Yet his gaze remained unswervingly ahead. If he knew where she sat, he gave no sign of it. Though it was she who’d warned him to avoid her, his aloofness plunged her into misery even as the sight of him made her soar into joy. Over the gleam of his armor his surcoat was blazoned with the Seymour arms. The plumes in his charger’s crest blew gay and brave in the breeze, but he wore no lady’s favor. He turned his head slightly, and for a fleeting instant his eyes met hers. Radiance poured into her. Isabel smiled, then made herself look away.

Through the far entrance rode Lord Adam Colford. His surcoat and his mount’s caparison fluttered crimson, but whose favor was the silver gauze wafting from his helmet Isabel neither knew nor cared. She had never known Colford to speak to, nor liked the cold arrogance of his bearing. Even had he not been her cousin’s enemy, he struck her as a hard man, his noble breeding unwarmed by any human feeling.

The combatants trotted the length of the tiltyard while the heralds announced their names and titles. Reaching the center, they pivoted smartly to salute the King and Queen, then gave the customary salute to each other. “There’s a hawker, go fetch me an orange,” Jane directed her serving woman, who went to obey, blocking the view. Isabel swallowed sharp words. When the way cleared, the two knights were poised, lances at the ready.

At the signal they charged. Wielding lances in one hand, shields in the other, they guided their mounts by the grip of their thighs, depending only on balance to stay in the saddle. Gravel flew from pummeling hooves, reminding Isabel of the dangerous footing. If a horse in full armor fell on its rider, death was near certain. As Tom closed with his opponent he raised his lance and couched it. Steel clashed. Isabel rocked forward as daylight showed between Tom and his mount. With a grinding crash he was down. Colford turned in the saddle. Even in the heavy armor the movement managed to convey a discourteously predatory satisfaction. Anxiously Isabel watched Tom’s esquire help him to his feet. Swaying, but upright beneath the weight of his armor, Tom Seymour drew his sword for foot combat.

Lord Colford dismounted. Undazed and possessed of dense, compact sinews to Tom’s tall slenderness, he had the advantage on foot, and Tom was not bound to go on with it. But Tom raised his sword. Chivalry demanded Colford should allow him to gain a point to salve his pride before striking in full force. Perchance, Tom could use that chance to grasp victory. Colford paused to make sure Tom was steady on his feet, then approached. But he did not make even a polite pretense of attack. As if bored with the whole matter, he glanced up at an approaching bank of clouds as if the weather for the evening’s entertainment were his only concern. Tom paused, uncertain what to make of it. A strike on an unguarded opponent would win him no glory, and he was not the man to take such an ignoble advantage. Or was Colford trying to make him do exactly that? Isabel knew of no quarrel between them, but the aristocrats of the old guard were always trying to show up ambitious gentry like the Seymours. Or perhaps, Lord Colford’s disdain extended to everyone but himself. Suddenly, his sword flicked. Tom parried, but Colford had not struck; it was only a feint. Isabel heard a few scornful sounds at Tom’s hot headedness, and clenched her teeth. Tom dared him with a sharp feint of his own, but Colford did not bother responding. Though his face was hidden by his visor, Isabel knew Thomas Seymour must be breathing fires of wrath. Yet he stayed himself when Colford’s sword flicked again. But this time Colford moved with it. Tom parried, but encountered only air and staggered. Seizing on his imbalance, Colford felled him with a single perfunctory stroke. Tom’s esquire assisted him to the far exit to cheers and snickers. Wrath scathing within her, Isabel looked to her father. He was a stickler for chivalry. He would surely show his disfavor at such a churlish victory. But no, he was chuckling as if he thought it clever. Lord Colford raised his visor, receiving his praise. He had won favor with the King. He cared not how, or at whose expense.

“The villain played his trick like a master.” Hugh pulled off a few sections of Jane’s orange and devoured them.

“A master of what? Scorpions? But what do you care, your wager’s won—and nothing proved but how easy it is to appeal to base instincts. The win was dishonorable.”

“Adam, Lord Colford,” Wyatt intoned. “You are challenged to a duel by Lady Isabel, Upholder of Honor, Good Manners and All That’s Fair. Choose your weapons.”

“Tongues!” Hugh answered. “My wager’s on you, coz.”

“Begging your pardon, sir,” a child’s voice distracted them. A freckle-faced boy of about ten stood in the walkway. “Are you Sir Hugh Lovell?”

Hugh turned, still smiling. “I am.”

“Then I’ve a message for you, sir.”

“Have you?” Hugh took the folded paper he was offered and handed the boy a farthing.

After the knavery in the tiltyard, Isabel would rather have swallowed poison than commit any dishonor, but she felt mightily annoyed when Hugh opened the note angled away from her. His blond brows lowered, then sprang up. “You’ll grant me your leave, ladies? I won’t be long.” Clutching the paper, he bounded along the walkway and down the stairs.

“There’s gallant protection for you.” Jane sucked on the last section of her orange.

At last Isabel spotted Tom Seymour entering the far side of the stands, where his brother Edward and other Seymour connections were. Anxiously she assessed the damage. His fair skin was whiter than usual, making his dark grey eyes startling under the russet of his hair. His face was controlled, but not drawn. He smiled as his brother clapped his back, but that was like him, whatever he felt. He sat tenderly, but not as if in severe pain. He had taken no grave hurt—at least, no bodily hurt. She ached for his pride.

“No wonder they’re taking so long to start the next joust. His Majesty’s gone.”

While the Queen chatted with her inner circle of Spanish ladies, he had wandered off, making a wager or two with his friends, Isabel supposed, as was his wont. Her attention went back to Tom. He drank from a flask his brother handed him, but did not glance her way. No doubt hers was the last gaze he wanted to meet just now. “May Lord Colford be afflicted with a plague of Egyptians!” She was somewhat mollified when Jane burst into merry laughter at her sleight of tongue.

At last King Henry reappeared, his gold doublet and white hose conspicuous as he moved through the crowd, his guards exhausted with the effort of keeping up with him. Resuming his seat, he exchanged a few words with the Queen.

“Something’s wrong.”

“What?” Jane asked. “His Majesty seems pleased with the games, now they’ll go on.”

“Marvelous pleased. But . . . his hose.”

“His what? Have you been too long in the sun?”

“No longer than it takes a chestnut to ripen.” Isabel’s curiosity pricked. Before, his hose were pale yellow. She would wager anything on it. Now, they were white as a swan’s plumage. But why retire to change hose? She frowned, piqued by this challenge to common sense. “Mark me, mischief’s afoot.”

Queen Katherine’s manner betrayed nothing, but Isabel watched as the King put forth a hand to receive his huge, jewel-encrusted cup from a page. The gesture was curiously placid, lacking the nervous energy she knew so well. “My father’s up to his old japes. That’s Edward Nevill!”

“No, never,” Jane answered with certainty, then frowned. “Well, maybe his shoulders aren’t so broad. But his face—no, it’s not His Majesty’s! Though they look so much alike that at this distance anyone could be fooled. You recognized him by his hose?”

“They were a different color before, so I looked sharper.”

“Your astuteness is close to miraculous.” Wyatt looked uncertain what he thought of such an accomplishment in a lady.

“No miracle, much toil under a very determined tutor. I can also calculate the area of a circle, remember the feast day of every saint, and translate Julius Caesar’s writings—for all the good it does anyone. I’ll never make a lawyer or priest, and my lord father will marry me to a dullard if it suits his purposes.” She glanced at the counterfeit king, noting now that his crown was also different, which stood to reason. Though King Henry allowed his kinsman to impersonate him for a rollick, wear his doublet, even drink from his golden goblet, a royal crown was sacred. Nevill’s must be an imitation, left over from some masking entertainment.

The trumpets blew. Isabel and her friends exchanged knowing glances as the jousters entered the lists; for the defenders, Sir Nicholas Carew in his fanciful helmet like a gargoyle’s snout, his lady’s favor flying from the crest, and for the challengers a knight with a closed visor, his armor a mysterious black. “Look at them.” Wyatt indicated the squinting, craning courtiers.

“Next they will scratch their heads in puzzlement,” Isabel said, and was rewarded when Sir Piers Knevet, sitting near the Seymours, chose that moment to do so. “I imagine it’s more than the fun of the jape,” she added thoughtfully. “The Privy Council carps against my lord father for risking himself at the tilt. I suspect he had a mind to escape their clack—at least, beforehand.”

“Afterward, he’ll say they’re too late.”

“And so they will be,” Isabel answered, smiling. She watched her father ride the length of the stands while speculation swelled to excitement. To see the King joust was rare these days, but he’d once been a champion. So had Carew, who’d embellished his own reputation with feats like riding across the tiltyard hefting a whole tree trunk for a lance. This should be a match, indeed.

About to salute the Queen and his counterfeit self, the Black Knight paused. His gauntlets went to his helm as if he only now noticed its bareness. Spurring to the stands, he bowed in the saddle to the nearest lady. She played along with his fancy, pretending to be taken aback at the alarming stranger, but nimbly unhooked the gold chain from her waist and tossed it. Catching it deftly, the Black Knight fastened it about his massive shoulders, saluted her with raised gauntlet, and rode back, to applause.

“I’m not the only one who has something in common with Will Somers,” Isabel remarked, feeling a touch of ironic affection.

The counterfeit king signaled, and the knights burst forward. Henry couched his lance, but his mount’s hindquarters floundered sideways. For a breathless moment horse and rider slithered on the muddy patch, then the horse went down. Isabel leapt to her feet, her temples pounding. Her father had been thrown clear, but he lay unmoving. His esquire reached him and unfastened his helmet. Isabel glimpsed blood before the competitors and esquires surrounded him, hiding him from view. Their silence was ominous. Her breath broken into painful shards, she whispered prayers, she scarcely knew what. Amid her fear she heard Wyatt’s quiet words. “If he’s taken from us, who will rule?”

Beyond her anxiety for her father, a nightmare landscape opened out. Princess Mary was only a child, and many felt Queen Katherine too apt to bend to the Emperor in Spain, who might swallow little England to feed his own ends. If they had their supporters, so did her half-brother Richmond, among those who would not stomach the rule of a woman. It would mean factions, bloodshed, the people now surrounding her killing one another, as their parents’ generation did in the Wars of the Roses. Please God, grant it may not be—

A cheer went up. Black armor glistened in the sun as King Henry stood, leaning on Nicholas Carew’s shoulder. They had bound a cloth about his forehead. For a moment he stood still, then with an impatient movement waved them away and sent an esquire after his horse. When the man brought it, he mounted. Isabel shouted in gladness, joining the general roar as her royal father galloped the length of the yard, proving he was uninjured.

But when he dismounted near the archway, he was swaying. Sir Thomas More descended the steps to his aid, and Colford’s brother, Sir Giles Colford, and the spectators were treated to the rare spectacle of Cardinal Wolsey himself puffing as he hurried down.

“Away, I’ve taken no hurt,” King Henry ordered, but Isabel could see the accident had shaken him. “Worrisome old women! A tumble or two is all part of the game.” Despite his bluster, the King steadied himself with his hand on More’s arm. “I scared you that time, eh Wolsey? And my good Giles?” His councilors answered too quietly to hear from where Isabel sat, exchanging glances of relief as they expressed as much of their anxiety as they dared. Henry laughed.

From beyond the archway cries arose. A palace guard burst through and fell on his knee before the King. “Murder! Treason!” he gasped. “Your Majesty, the Sun and Stars! Two guards lie slaughtered, and your crown is stolen!”

© BearCat Press LLC.